Love Lane Lives

The history of sugar in Liverpool and the effects of the closure of the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery, Love Lane

Bitter Sweet Pensioner Stories

Written by Ron Noon at 14:39 on Wednesday, June 10th 2009

BITTER SWEET PENSIONER STORIES

Written by Ron Noon in 2004

This is a saccharine tale of contrasting retirement fortunes for employees of the sugar giant, Tate and Lyle, a multinational company before the term was shoehorned into the lexicon. It acquired the Royal imprimatur, mainly because of its famous founder, Henry Tate, a fabulously wealthy Victorian sugar baron, philanthropist and legendary patron of the arts. His name in 2004 is the logo of the Tate Modern rather than Tate Sugar and for most people the only thing that matters about the latter is its sweetness. That is the last thing to be said about a unique and intensely political product’s history. In six centuries of global expansion, so many tears have been shed in sugar’s name that it ought to have completely lost its sweetness. But for Larry Pillard, Tate’s American chief executive officer from November 1996, the world was very sweet, as on 1 January 2003, he started drawing his company pension at the middle age of fifty-five.

Vera Noonan* is the daughter of a working-class employee who tragically drowned in the River Thames in 1990, after falling from a crane at the company’s massive Silvertown refinery. At the beginning of November the thirty-one year old mother of Ron’s* three grandchildren avoided an immediate custodial prison sentence, although she was found guilty of drawing £14,000 of his pension. It transpired that for two years after mother Julia* died in 2001, Vera swindled the sugar giant, and as she told the jury at the Old Bailey, it was because of a determination ‘to make them [Tate and Lyle] pay for her father’s death’. The demand for reprisal is not the most noble of emotions but it is more ‘natural’ than the spurious claims made by sugar industry school misinformation packs, that refined sucrose is a pure and ‘natural’ product. The prolonged crushing, purging and laundering process that transforms sugar beet or sugar cane into the whitestuff, is decidedly ‘industrial’ and sadly tainted by more than the blood of African slaves.

There are other sources of sweetness and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), derived from the wet milling of corn, was the first major biotechnology breakthrough in the sugar world. It immediately proved a lucrative sweetener in the American soft drinks market and Tate’s in 1988 acquired, in a hostile leveraged takeover, a major supplier - the Decatur, Illinois based AE Staley Manufacturing Company. The spur to the acquisition of Staley’s four major corn processing sites was to remove the competition and as with so many other multinationals obsessed with global competitiveness, Tate’s proceeded to follow the industrial relations low road of keeping wages down, undermining social safety programmes and environmental and workplace safety.

The result of the ‘war on the workers’ was that on 27 June 1993, a new chief executive officer, brought in from Cargill, a rival agribusiness colossus, locked out 760 union employees in Decatur. A lockout is the ultimate weapon of mass destruction deployed by employers against unions and this one took thirty months before corporate solidarity won. Not only was the union ‘downsized’ but Tate’s attained more flexible labour practices through the ‘time-theft’ of rotating twelve-hour shifts demanding conformity to the company calendar rather than the more natural work rhythms that made family and social life predictable. Larry Pillard who in his teens had wanted to be a dentist, had extracted the teeth from a concerted and admirable community effort to save union jobs, and was rewarded for resolving the aching Staley problem by promotion to the top job in London, taking over from Sir Neil Shaw in 1996.

There was no safety net to break Vera’s dad’s fall and it was ten days before his body was recovered from the Thames, only for the bereaved family to be torn apart by his cruel and preventable death. There is no anaesthetised pain when health and safety issues are ‘downsized’ and 1990 was a bad year to be a Tate’s employee. In Decatur, Illinois Jim Beals was killed by inadequate health and safety measures, while in Greenock a worker was smothered to death by an avalanche of sugar inside a silo. The tragedy in Scotland was so serious that the case was one of the rare workplace injury cases to be held in a crown court, resulting in a swingeing fine for Tate and Lyle.

In Decatur, plumes of smoke from forty-five acres of ‘chemical plant’ dust the downtown ‘with a scent as sweet and thick as a bakery’s’, but the dusts and vapours inside the plant were often invisible to workers. Safety measures were not in proper order when toxic propylene oxide gas was released into the cornstarch-processing tank in which Jim and another worker were making repairs. The awful irony here was that Jim had written up a grievance report on the handling of propylene oxide in the plant the very afternoon that he was killed. His fellow worker, Gerry Summer, described how on that fateful day not one of the fifteen ‘Scott airpacks’ in the plant was charged over thirty per cent, rendering them useless in an emergency, and that ten bottles of oxygen on the wall outside where they had been working, were all subsequently found to be empty. In January 1991 the Federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, issued a $1.6 million fine against Staley based on 298 ‘serious and wilful infractions’.

The judge at Vera’s trial admonished her that ‘in the normal course of events this sort of theft … could have resulted in an immediate custodial sentence’. He was prepared to show leniency however, because after the company audit that led to her arrest, she candidly admitted to being a pensions cheat, and so her sentence was nine months jail, suspended for eighteen months. The jury had been told that the pension money was drawn because her father’s death had not only caused her mother to give up on life but her brother had gone to pieces and developed a serious gambling problem. This East End world of Newham and Silvertown was far removed from the terrain of ‘executive pensions excess’ and Larry Pillard’s west end Chelsea home.

Pillard’s career started at rival HFCS producer Cargill, before the promotion at AE Staley in 1992. By 2003 he was opening a lucrative pension account and an even higher paid position as executive chairman of Swedish group, Tetra Laval. This food packaging firm is owned by Hans Rausing, a Swede allegedly one of the richest men in Britain. He has lived here since 1982 but his home, albeit, a purpose-built palace in East Sussex, is not legally his ‘domicile’, according to his hired tax advisers. As the Guardian newspaper revealed in 2002, ‘with this one, vital, verbal distinction, he escapes paying tax on all his income and on all his capital gains in all the world outside the UK’. Larry Pillard and Hans Rausing live in a parallel and unfathomable world to ordinary pensioners and the young mother branded a ‘pensions cheat’ at the Central Criminal Court.

At the end of that first week in January, Vera’s pensions scam would have netted her about £134, well short of Larry’s legal £6,000. Financially Larry was looking on the bright side as in 2002 a £503,000 base salary for the nine months down to the end of the financial year, had been boosted by a £431,000 bonus, part of which was the pensionable ‘discretionary’ award from Tate’s remuneration committee. This audited arithmetic was out of sight and out of the public mind until a report published in the London Evening Standard on the 27 June 2003, revealed, that the man vilified as a union buster in Jim Beals’ old workplace in Decatur, had received from Tate’s, ‘a £1.5 million pension sweetener’ after unexpectedly announcing he was stepping down as chief executive of the sugar giant. Allegations were heard that the timing of his move might have been related to an imminent class action case in America about the rigging of HFCS prices, by ostensibly rival companies, when he was chief executive at Staley.

Larry’s sums shaded Vera’s £134 a week con, but company accountants were nonetheless adamant, that there been no backdoor settlement and no compensation, paid over to the ‘colourful Harley Davidson motor bike fanatic’. Pillard had simply ‘elected to exercise his right under the US pensions plan to draw his pension early’. (Ron’s family drew his pension early but obviously not through choice.) The Evening Standard’s view of the accounts was that ‘£1.5 million was added to his £2.36 million pension pot’ to allow Larry to draw his pension in the new year. A £311,000 annuity is a more than ample amount to enter life’s third age and Britain’s wealthiest pensioners club. As a working pensioner at Tetra Laval the pin money was useful for the maintenance costs of his home in Chelsea and farm in Iowa and paled the £67,000 housing allowance plus transport costs that Tate’s had paid him the previous year to facilitate family flights to America.

Sadly there are far too many cases of executive pensions excess falling below the radar of public scrutiny and which never end up in an Old Bailey trial. Warmly persuasive phrases such as corporate social responsibility slip off the public relations tongue too easily, whereas very little evidence can be found of investor anger over the stark disparity between executive munificence and employee privation. There was no displeasure - let alone anger - evident in the Royal Lancaster Hotel at the 100th Annual General Meeting of Henry Tate’s once proudly paternalistic company, when shareholders approved Pillard’s controversial retirement package.

That justifiable ire and outrage was sadly absent at the end of the last millennium when Liverpool Tate’s pensioners literally had Christmas stolen from them. They were told in an official company letter in October 1999 that the biennial Christmas bash at the Britannia Adelphi Hotel on 2 December would be the very last one. Albert E Sloane, the seventy-seven year old sweet fighter who led a ten year struggle to keep open Love Lane refinery, the mother plant in Henry Tate’s sugar dynasty, was incandescent with rage. This lifelong socialist never secured a job after the Lane was closed in 1981 and there was a sense of déjà vu that Tate’s history on Merseyside was repeating itself as another tragedy.

The junking of the biennial company-sponsored Christmas party symbolised a Scrooge-like meanness of spirit. That was certainly what Frank Till felt like when he expressed his sadness at the last supper. ‘The people who run Tate and Lyle now are just names to us. Previously we knew them - Saxon Tate, Colin Lyle, Nicholas Tate - we knew them all, but not now. They are unidentifiable people and of course we are unidentifiable to them.’ Frank was a sweet fighter who had joined Tate’s in 1941 rejoining in 1947 after service in the RAF. Albert’s wartime experience had been in the RAF and coincidentally he followed his father into the ‘sugar mill’, the same year Frank returned.

On a beautifully sunny Thursday afternoon, a weekend away from Christmas 2001, when Tetra Laval was presumably not even a twinkle in Pillard’s eye, an unusual labour petition was hand delivered to the receptionist on the second floor of Sugar Quay, the company’s multi-story headquarters looking out over the Thames and a wonderful view of the nearby Tower of London and Tower Bridge. Addressed to the company chief executive it called for restoration of the ‘biennial Christmas reunions’ for pensioners in Liverpool. The majority of these former employees had devoted most of their working lives to the charmingly-named Love Lane refinery, which in the eighteenth century, when Liverpool was at the epicentre of the infamous transatlantic slave trade, was a perambulating maidens’ and ladies pathway. By 1872 the lane was cut through by the Leeds-Liverpool canal and amongst glue factories and warehouses warped into the mother plant in Henry Tate’s sugar empire. Sadly at the end of the last millennium a letter from John Walker, the chief executive of Tate’s European division, announced that ‘regrettably because of the need to continually review and reduce costs’ the 1999 Christmas bash would be the last.

Albert had lived his working life as a free spirit not a cost of production, but sadly ‘commodity status’ was the objective reality for all the 1,500 workers junked in 1981. Many like him never secured another job but enthusiastically looked forward to the ‘craic’ and the ‘associational’ benefits of the annual and then biennial Christmas reunion. Walker’s rationale for the end of Christmas angered them all. Ominously as the pensioners gathered together beneath resplendent streamers strung across the banqueting hall of a once quite magisterial hotel, the cold business logic that deemed this their last supper was matched by the freezing weather outside.

The costs of these Christmas bashes had always been ameliorated by the demographic fact that it was an ageing labour force in 1981. Unsurprisingly the first topic of conversation at the Christmas bashes was of the latest toll of bereavements, but it was part of the ritual of reliving their memories and stories of the world of work and the age when they had helped sweeten the nation’s breakfast tables. John Maclean, Albert’s close friend, wryly commented that not only did ‘Christmas come round every two years with Tate’s’, but ‘each time, absent friends meant that it got cheaper. We never thought they’d scrap it altogether though’. The vainglorious efforts in 2001 to force a company rethink and bring back Christmas were totally ignored despite the terminal demographics. Bob Bannister another former shop steward like Albert asked at the last supper on Lime Street whether it would ‘spoil some vast eternal plan if these Christmas get-togethers were to continue … after all, in ten or fifteen years most of us will have left for greener pastures’.

There have been no hats off to Larry in Liverpool from the old boys and girls from the whitestuff, and ironically one of the signatories to the petition was Alan Bleasdale, the local playwright who rose to national fame in the early 1980s with his magisterially bleak The Boys from the Blackstuff. The award-winning series demonstrated more effectively than the unemployment demonstrations of the early-1980s, the sheer waste, futility and demoralisation of being without work in Thatcher’s Britain - especially in a city tagged the Bermuda Triangle of British capitalism. In the closing scene filmed on the actual day when the refinery was being bulldozed to the ground, Chrissy, Logo and Yosser (‘gis a job’) Hughes are seen leaving a manic pub redundancy party in the Green Man, and tramping disconsolately alongside the refinery walls. Despite Bleasdale’s impeccable craft skills, the irony was that the writer was only subliminally aware of the proxy voices of the boys and girls from the whitestuff who had departed a year earlier. ‘What’s going wrong Logo?’ asks the dejected Chrissy. ‘Everything la, everything.’ If Bleasdale had beamed up with Scotty on to the Starship Enterprise it would have had more credibility than the notion that this one time ‘family firm’, where sometimes three generations would be working at the same time, would in the future scrap Christmas.

Sadly the 2001 petition was deemed unworthy of even a reply from Larry Pillard or John Walker. The latter had at least been prompted earlier on in 2001 into replying to working-class scribe and pensioner Peter Leacy, who unlike many others had continued to work, as a tanker-driver for Tate’s at Silvertown, Greenock, Millwall and Manchester, until retirement in 1993. In a letter dated 1 January 2001, addressed to the chief executive, he emphasised his experiences as a pensioner visitor for the company and how ‘I encounter hundreds of regrets at the ending of the biennial Christmas reunions … May I therefore prevail upon your good self, and your fellow directors to stage a final, one off, never to be forgotten farewell to Love Lane party at the very place of so many happy get-together’s … the Adelphi Hotel’. Walker thanked Peter for the letter, which the chief executive had ‘passed to me to reply to you’ but regretted ‘you may have read the company is having very difficult times … and in these circumstances I don’t think we could justify the kind of expenditure that such a party would require. In more prosperous times, this reply might have been different’. (My italics.)

In the letter accompanying the petition to Pillard at the end of 2001, I had mentioned that unhappily Mr Leacy had suffered a stroke and his eyesight had badly deteriorated. We had nevertheless ‘decided that it would be worth one final effort to try to persuade your company to re-establish this much cherished biennial event … As an academic I do not have the same “property” in the subject as Mr Leacy and the other boys and girls from the whitestuff, but I fully understand the pain and regret constantly expressed by those interviewed. The sale of Domino and last month’s announcement of a strengthening financial position, reflected in an upward movement in share price, suggests that next year with accompanying generosity of spirit, a party could be financed.’ Miserably over the last five years, generosity of spirit has been the most conspicuously absent Tate’s trait.

More prosperous times have officially arrived for this world leader in carbohydrate processing, and the Evening Standard on Monday 6 December announced that it ‘is expected to make a triumphant return to Britain’s top 100 companies index this week’. As one of the few original FTSE companies, this seasonal cheer coincides with news that its breakthrough non-calorie sweetener, Splenda, is doing so splendid in terms of sales, that it is unable to keep up with demand for it in the US. Its first half of year profit fell however after the company settled what the Washington Post described as ‘the biggest food anti-trust class action in US history’. Archer Daniels Midland, the biggest institutional shareholder in Tate’s, and Cargill, another ostensible competitor, settled in May and June. Staley settled last and, while Tate’s legal team protested its innocence of price-fixing allegations, knew that if the case had gone to trial, damages could have reached $4 billion. The out of court settlement of $100 million ‘had been agreed for pragmatic reasons’. How ironic that Staley had tried to legitimise its draconian actions in 1993 as being dictated by the pressure of global competition.

Henry Tate’s paternalistic company died a long time before the junking of Love Lane in 1981. Its vestigial relics were the biennial Christmas bash at the Adelphi, the continued mantra-like exhortation of the company’s work in the community and the value attached to present and past workforces. That representation is sadly at variance with the reality of this story of pensioner politics, which are not only distinctly asymmetrical, but demand urgent redress. And this year, just to compound that asymmetry, Vera Noonan was stigmatised a ‘pension cheat’ for drawing £14,000 on her dead father’s company tab, while the company paid £56 million to conclude some unfinished business from Larry Pillard’s days with AE Staley.

After the historic pensioners’ last supper on Lime Street, in December 1999, a number of ex-refinery workers adjourned to a pub aptly named the Beehive. The mood of terminal nostalgia had been broken by angry defiance and Albert urged the sympathetic but by then well-inebriated sugar researcher to make Tate’s pay for ‘robbin’ Christmas from us’. Predictably in December 1999 and December 2001 when the petition was hand-delivered to Sugar Quay, the petty cash expenditure to fulfil historic obligations to Love Lane workers was not a sexy subject for the media to champion and pragmatic enough a cause for the company to reply to let alone comply with.

That said, for the old boys from the whitestuff, Albert, John, Bob, Frank and Peter, Larry Pillard’s executive pensions excess is now no longer the final painful reminder of the transformation of that soulful family firm they dedicated their working lives to. Last Thursday afternoon, when the old guys got together for an unofficial Christmas bash, in the Beehive and Punch and Judy pubs, the tragic case of a young mother of three, branded a pensions cheat, warranted a respectful solidarity toast to her father’s and mother’s memory. But then who would not wish to ‘get even’ with a company that officially killed Christmas in Liverpool, the historic home of the Tate and Lyle sugar dynasty?

..........................

* Vera, Ron and Julia are not the real names of the people involved in that tragic case involving plaintiffs, Tate & Lyle and the unfortunate defendant and young mother in South East London. The anonymity of that proud, dignified and respectable woman demands protection.

............................................................................................................................................................................................................................

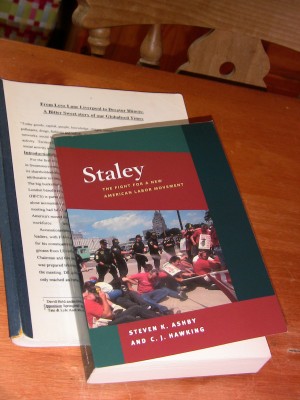

If you want to know more about what happened at Staley in Decatur Illinois then this new book by Steven J Ashby and CJ Hawking is the one to try to get hold of. It’s not been published in Britain yet but is in its second print run in the States after only two months since its release!