Love Lane Lives

The history of sugar in Liverpool and the effects of the closure of the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery, Love Lane

George’s last ride and Love Lane Lives

Written by Ron Noon at 14:13 on Wednesday, November 07th 2012

Tonight is exactly 30 years since Alan Bleasdale’s award winning series, The Boys from the Blackstuff, finished its first run on BBC2. “George’s last ride” was its final and unforgettable last episode and it made for more than just brilliant television drama. It articulated a zeitgeist of seemingly terminal economic decline for the once proud port city in which it was set, and more threatening than the disappearance of jobs, were lost hopes and dreams of battered and bewildered communities, in what figuratively was dubbed “The Bermuda Triangle of British Capitalism”! Chrissie one of the key characters in the series asks “what’s going wrong Logo, what’s going wrong” and the unequivocal answer was “everything la, everything”.

In the Sixties, the Merseybeat sound conquered the musical world and for fifty one weeks between April 1963 and May 1964 there would be a recording by a Liverpudlian artist at Number 1 in the charts, one understandable reason why we played a pivotal part in the so called cultural revolution that liberated that decade. Despite the Beatles the basic economic fact was that unemployment in the musical capital of the world was twice the British national average. So despite the world wanting to hold a Beatle’s hand in what seemed its musical apotheosis, the city and the Merseyside region in general in the 20 years that followed were ravaged by fallout from severe global economic recession. Between 1966 and 1977 no less than 350 factories in Liverpool closed or moved elsewhere, 40,000 jobs were lost and between 1971 and 1985 employment in the city fell by 33 per cent. The little ditty doing the rounds in the early 1980s and expressed in the Scotty Free Press was: “Redundancies here, Redundancies there, Redundancies, Redundancies everywhere”.

As Jon Murden expressed it in Liverpool 800, “from the docks to flour milling and telephone equipment, from office equipment to animal foods, there had been job losses and factory closures and as one British Leyland worker expressed it in 1980 two years after the Speke factory had been closed down, ‘I don’t know what’s happening. It seems like there’s just nothing doing for this town’. By the early 1980s most of the dock system had been changed and converted to other uses. The port that had created [modern] Liverpool had dwindled to insignificance and left the city with huge economic and political problems.”

A national tabloid 27 days before George’s last ride appeared on our screens asserted that “they should build a fence around [Liverpool] and charge admission. For sadly, it has become a ‘showcase’ of everything that has gone wrong in Britain’s major cities.” (Daily Mirror 11.10.1982). Whether depicted as showcase or basket case, the enormous condescension of media coverage was as widespread as the government policy of “managed decline” for the former gateway to empire, was top secret! The clichéd references to “Merseyside militancy” and so called “generalised apathy” had been trotted out with strike statistics that purported to show that the leaving and grieving of Liverpool was a self inflicted wound which the truculent workers had only themselves to blame for. (Tate & Lyle had not had a serious industrial relations hiccup since the 1926 General Strike and the company was subsequently found out as the biggest recipient of regional aid and assistance between 1975 and 1980!)

Not all newspapers indulged in the scapegoating. “The question that remains to be answered is why, when companies choose to rationalise, the blow so often falls on Merseyside?” That question posed by the Financial Times was a means of moving the focus from subjective phenomena into examining structural explanations, such as the make up and mix of industries in the local economy and Merseyside’s proneness to external decision making, particularly given the large numbers of MNC branch plants based here. In 1980 a collaborative and interdisciplinary project involving members of the University of Liverpool and the then Liverpool Polytechnic wrote and published…Merseyside in Crisis. In the book, the authors, (and I was one of them), attempted to elaborate the scale of the socio-economic disaster that Merseyside was experiencing at the time, and not only seek to explain the historical roots of this ‘crisis’ but how references to “Merseyside militancy” and “mindless militancy” were a reversal of cause and effect. We addressed over 100 meetings in the Merseyside area to publicise and sell the book & 5,000 copies were sold within 18 months, the vast majority within the locality, and mostly to a non-academic readership. We argued that “if the Government’s own estimates of 40 per cent unemployment are anything to go by, Liverpool looks set to become the Jarrow of the 1980s”! Was it any wonder that the People’s March for Jobs began in this city in May 1981?

18 months later and our city was decidedly on the ropes and the woman quoted at the beginning of our film declared, “It’s dead now”. She meant Liverpool not Tate & Lyle which simply closed Love Lane refinery down and witnessed its share prices go through the roof! The actual refinery 30 years ago tonight was filmed being bulldozed into oblivion leaving what Albert Tod Sloane had warned in 1971 would be “a dirty big hole in the community”, impossible to fill. Bleasdale may have been subliminally aware of those proxy voices, of the 1570 boys and girls from the whitestuff who had gone down the road on April 22nd 1981, but the physical destruction of the refinery and use as background to yet another manic pub redundancy party in the Green Man, seared itself into the nation’s consciousness more effectively than the national unemployment demonstrations of the time. I wonder whether the character of George Malone was? The character of Yosser “gis a job Hughes” proved to have the longest shelf life but why not George?

The actor that the scouse Dickens used to play George Malone was Peter Kerrigan, a former Liverpool docker who played with pathos and grit the dying docker who ended up on the Blackstuff (tarmac), because of victimisation for his socialist beliefs. George stood for his class and the dignity of labour refusing to give up on those collective hopes and dreams in a remarkable speech delivered as he is being pushed by Chrissie in a wheelchair ride through the then derelict and decaying, now magnificently refurbished, Albert Dock. His superb cameo performance was based partly on Kerrigan’s own experiences* and a crafted Bleasdale script that articulated like a lorry over all those who were responsible for the death of George’s dreams.

Here’s the script version:

Saturday dinnertime and not a soul about. Once upon a time, Chrissie, once upon a time, Saturday afternoon, we’d have been looking forward to it from the previous Saturday. Payday Saturday, you know. No five-day week and then off to the leisure centre then, boyo.

Oh, there’d be hundreds coming along here. There’d be the ship-repair men, the scalers, the dockers, the Mary Ellens who used to swab and clean the big liners, and right behind us there’d be them great big shire cart horses.

There was many a good old horse went down the hill but he came back up in the knacker’s carts. The vet had put a gun to his head, a straw bolster around its neck and he’d wind it up into the knacker’s cart. As its big head was turning, you could see the whites of its eye.

And yet those horses of privilege, who just pose outside Buckingham Palace and ponce and parade up and down the Mall! They were turned out into a meadow, of cowslip and clover, and guaranteed a full proven bag for the rest of their lives! Ah, Chrissie. It just seems like soddin’ yesterday.

The midday fun ... the women sandstoning the steps the flags. And the little kids playing allalley-oh. And the shops on the corner where you got your three pennyworth of fine Irish, the old snuff and a twist of tobacco. Your old gran had a nice flat top cart there. She used to sell salt fish and a big barrel of ribs straight off the pig’s back from the Irish boats. And then on the third Saturday we’d have the organ grinder and his monkey.

And there we’d be. All piling into Nellie’s or Pegleg Pete’s for a couple of pints of good beer. Maybe the first in the week. And we’d have the craic. Oh, the craic. We’d talk about many things … (Chrissie buts in with “of cabbages and kings!”).. of politics and power. And come the day we’d have inside toilets and proper bathrooms.

Of Attlee, Bevan. Hogan and Logan, the Braddocks and Dixie Dean. Lawton, Liddell. Matthews and Finney. Of “come the revolution” and the Blackpool Illuminations. Joseph Jones had a violin. A Stradivarius, he said!

Well, we’ve got our bathrooms, at considerable expense. And I write letters to prison for the mother of a man who rapes little boys. And there’s hundreds of friggin’ rapists still running free…

47 years ago, I stood here. A young bull. I watched my first ship come in. They say that memories live longer than dreams. But my dreams, those dreams of long ago … they still give me hope, and faith, in my class. I can’t believe that there’s no hope. I can’t…

Neither can I and the Love Lane Lives project, the recorded experiences of the boys and girls from the whitestuff and the rise of the Eldonians in that devastated sugar land community, prove that community and indeed “virtual community” is far more resilient than bricks and mortar that were Bleasdale’s stage props back then.

*Peter Kerrigan wrote a pamphlet, in 1958 entitled “What next for Britain’s port workers?” It’s the apprenticeship of so many Peters and Georges who’d witnessed at first hand the “blight of casualism”. This is what he writes: “Older men on the docks remember the thirties very well. The humiliation of the stands. The ‘muscle feeling’. The scramble for a job. They remember the ‘blue eyes’ system - the whisper of ‘You’re staying behind’ into the ear of a favoured one. The militant was isolated. The man who refused to overload a sling on the last ship was left standing.”

................................................................................................................................................................

Today has witnessed the death of another George’s dreams but whereas Romney’s are hopefully buried Malone’s may have Lazarus like been revived.

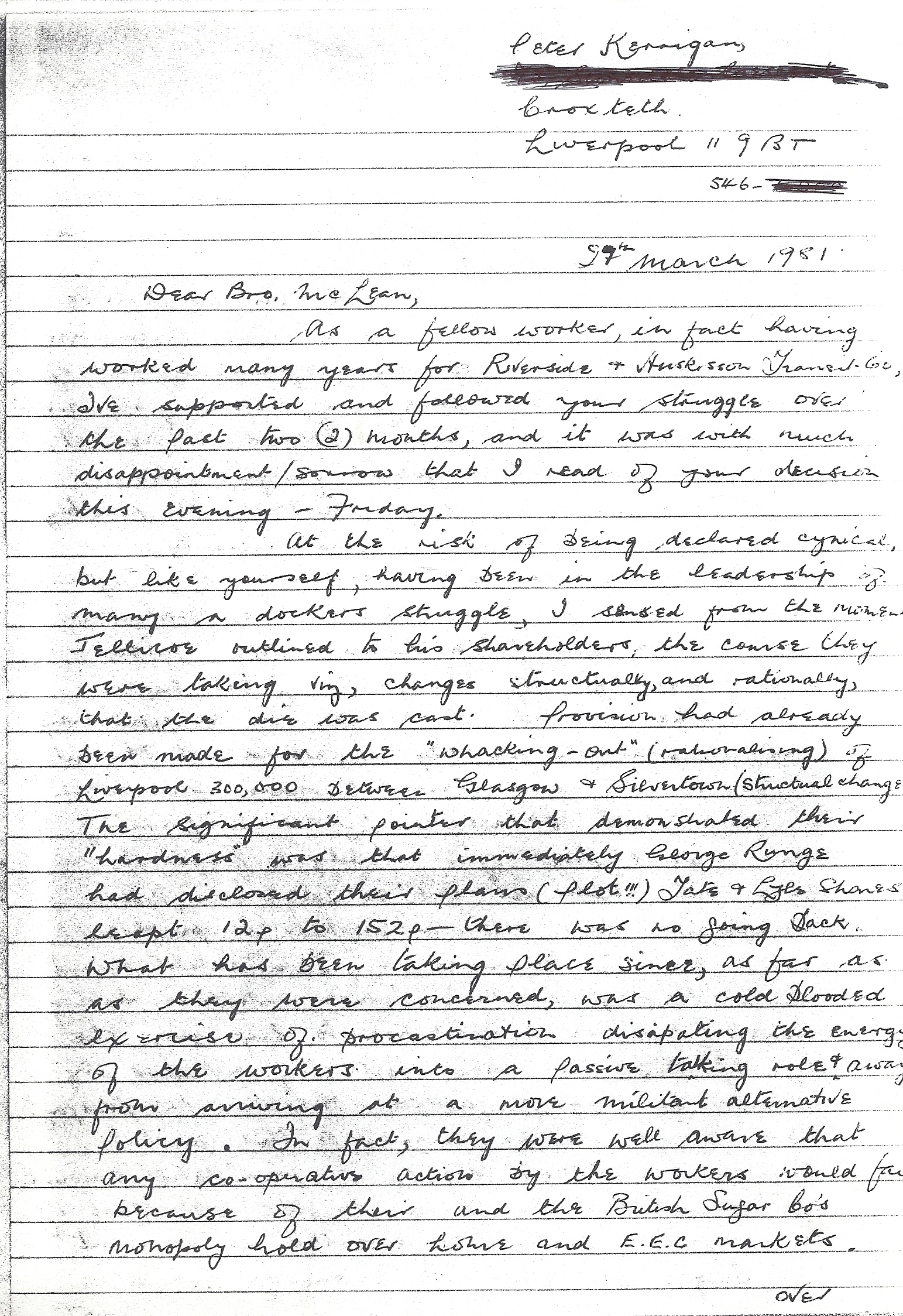

One thing that is not so well known about Peter Kerrigan is the fact that he was a great supporter of the refinery workers and wrote this letter in copper plate handwriting style to John Maclean.

Here’s the full letter in this pdf file.

Peter_Kerrigans_plea_to_John.pdf

A review of Merseyside in Crisis in Tribune. The price was £1 not 95p!