Love Lane Lives

The history of sugar in Liverpool and the effects of the closure of the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery, Love Lane

Last day of Black History Month 2009

Written by Ron Noon at 20:47 on Saturday, October 31st 2009

“Sugar did not create Negro slavery. Given the circumstances in which the New World was colonised by Europeans, the need for labour in the colonies for purposes other than sugar production and the long standing existence of slavery in Africa, African slaves would no doubt have been carried to the Americas if the sugar cane had never been domesticated. But the gigantic scale of the transatlantic slave trade and its maintenance for several centuries, were due primarily to the demand for sugar in Europe and North America.” W.A. Aykroyd Sweet Malefactor (1967)

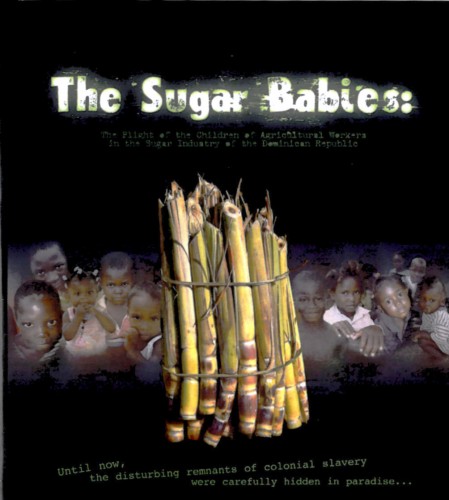

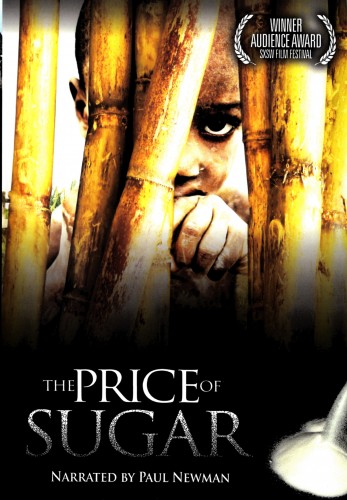

The first blog on this website, (November 27th 2008), highlighted the formidable obstacles impeding the wider distribution of two shocking films about modern day sugar slavery. “Bill Haney’s film ‘The Price of Sugar’ narrated by Paul Newman, and Amy Serrano’s ‘Sugar Babies’ are bitter sweet films dealing with abuses of human rights on sugar ‘bateyes’ in the Dominican Republic that…demand the oxygen of publicity.” Unlike our Boys and Girls from the Whitestuff, these films aroused blatant opposition and resistance from offended “sugar interests”.

Paul Newman’s last film was shown to interested students and staff at the end of October last year in the Clarence Street Lecture Theatre and a year later I introduced Serrano’s Sugar Babies, narrated by Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat, to a small audience at the FACT in Liverpool. Both of these incredibly important films were shown in Black History month and deal with the denial of birth rights to children born to Haitian parents on the sugar bateyes of the Dominican Republic. Both of these films deal with the remarkable Spanish priest, Father Christopher Hartley who spent ten years of his life among Haitian sugar cane cutters campaigning to win better conditions for them and who rapidly became a thorn in the side of the powerful sugar baron families, the Dominican Government and eventually his own church! “The human rights abuses I encountered there, were nothing I could have steeled myself for in advance” and “I would be a horrible man and a worse priest if I turned my back and did nothing.” Amy Serrano’s award winning film does not hold back in “naming the culprits” and she denounces not only the powerful Sugar families but the Government of the Dominican Republic “for criminal involvement with human trafficking”.

In an essay that appeared this summer she movingly reminds us of what is tragically not just a history lesson. “I linger on haunting portraits of stolen lives on modern day sugar plantations where ideas of freedom and self determination are but lofty concepts given the economics of dark skin. I dwell on easy recollections of starving children running into near seven foot high cane fields at noon, disappearing into the green as they scavenge for edible stalks to feed their daily hunger. I recall barefoot children venturing deep into those fields, vulnerable to cuts from the razor sharp blade of the cane and the bites from infectious rodents endemic to the sweet terrain”. She’s not only a talented film maker but an incredibly brave one too, determined to plug the past into the present and shake us out of a complacency that confines these abuses to museum exhibitions and transatlantic slave galleries! Her film “portends not only to deeply examine the disturbing modern day relations that continue among sugar, power and human rights…it equally strives to bring about sufficient awareness of how the past intersects the present, and how the future might be made right – at least for the children”. Who could deny the basic human rights of those children?

THE BOSTON BAY STATE BANNER

Febuary 14, 2008 – Vol. 43 No.27

Dominican sugar tycoons knock films critical of trade

Jonathan M. Katz

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — The Dominican sugar industry is striking back at two documentaries that depict Haitian cane-cutters working in dangerous conditions for little pay in the Dominican Republic.

The two films — one narrated by actor Paul Newman, the other by Haitian novelist Edwidge Danticat — echo U.S. State Department and Amnesty International reports that criticize the general mistreatment of Haitians who migrate over their shared border to the Dominican Republic on the island of Hispaniola.

The films have not been screened on the island, but Dominicans have lashed out at them nonetheless. When “The Price of Sugar,” narrated by Newman, was passed over for an Oscar nomination in January, Dominican newspapers widely quoted a sugar group celebrating that “justice has been done.” Industry insiders also were pleased when “Sugar Babies” was dropped from the program at the upcoming Miami International Film Festival.

Leading the effort to counter the movies’ impact are the Fanjul and Vicini families, who own the first and second-largest Dominican sugar companies, respectively. The Cuban American Fanjul family also owns vast sugar operations in Florida where Haitian workers on temporary U.S. visas harvest cane.

The Vicinis hired the Washington, D.C., lobbying and law firm of Patton Boggs to sue the makers of “The Price of Sugar” for defamation as part of their public relations campaign.

Dominican politicians are also getting involved. Foreign Minister Carlos Morales Troncoso, a former sugar magnate, called a Paris exhibition that displayed the two documentaries “a campaign of hate.”

“Their goal is to stop people in the world from seeing the movie, because it reveals conditions that viewers find deeply troubling,” said Bill Haney, who produced the Newman-narrated film, in a phone interview from Boston.

Patton Boggs attorney Benjamin Chew said the growers simply want to stop the spread of false allegations.

The Vicinis — heirs to a late Dominican president — say “The Price of Sugar” includes staged scenes, misrepresented photographs and footage of other companies’ workers.

“I tried really hard to tell the truth,” Haney countered. He said he met with the Vicinis for two days, offering to correct any major errors. He said they raised no major objections, and sent him a letter thanking him for being so open-minded.

Patton Boggs also wants to force “Sugar Babies” director Amy Serrano to turn over conversations with Haney, advocacy groups and workers. Serrano said last week that she was aware of an attempt to subpoena her, but had not been served.

She has faced difficulties airing her own film, which makes similar allegations of mistreatment at the Fanjuls’ companies in the Dominican Republic. On Jan. 25, the Miami festival told her it was removing the film from its program, without explanation. Festival organizers declined to comment to the AP.

The Rev. Christopher Hartley, a Catholic priest who worked with the cane-cutters for years and is featured in Haney’s film, told the AP in a phone interview from his new mission in Ethiopia that Haitian cane-cutters continue to live in “despotic misery” in the Dominican Republic.

But Chew said the criticism will only hurt the Haitian workers — a theme both sugar companies are focusing on.

A spokesman for the Fanjuls’ companies said they now provide free health care and schooling for the 35,000 workers and their families on company land. The Vicinis announced in 2006 they would build 500 homes with medical and other services, though construction appears to be in its early stages. And the Dominican Sugar Institute trade group posted photos online implying that life in the cane fields is better than in Haiti’s slums.

Thousands of Haitian cane-cutters live in state-run compounds known as “bateyes,” and while previous reporting trips to these places revealed poverty, overcrowding and numerous untreated field injuries, an Associated Press photographer visiting some Vicini bateyes last month found children had access to school and medical care.

“By urging Americans to ban Dominican sugar, the misguided filmmaker harms the very people whose cause he purports to advance,” Chew said about Haney’s film.

Gaston Cantens, spokesman for the Fanjuls’ Florida Crystals Corp., said Haitians would be harmed by “Sugar Babies” as well.

“The easy thing, perhaps, would be to go in there and kick everyone out and say, ‘We’re knocking this thing down, we’re going to mechanize,’” said Cantens. “That’s something that people like Amy Serrano don’t take into account.”

But Danticat — who recalls her family members returning sick and injured after years in the Dominican fields — said the companies should do much more.

“The only thing these children have to look forward to is death,” she said in a phone interview from Miami, where she lives. “That should make people angry. I don’t know why that doesn’t anger them more than the bad press they’re getting.”

March 6, 2008 — Vol. 43, No. 30

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

An historical perspective on the sugar trade

It used to be the only thing that mattered to me about sugar that it was sweet. But today that is the last thing I would say about either its history or the industry that continues to produce the achingly addictive, but perfectly legal drug (“Dominican sugar tycoons knock films critical of trade,” Feb. 14, 2008). “Sweet” is the last word I would use to describe a tainted product and the harsh conditions under which it was, and is still, produced. But the journey from field to breakfast table has not been sexy enough to merit much filming before “The Price of Sugar” and “Sugar Babies” incurred the wrath of vested industry interests.

These sadly predictable responses from Big Sugar’s hired prizefighters threaten to prevent a much-needed public debate about the true price we pay to fuel our “naughty but nice” addiction. Teaching a course on sugar and slaves in Liverpool has meant facing up to a past in which “there was not a stone untainted by the blood of African slaves.”

That is how we strive to redress selective historical amnesia in the former epicenter of the slave trade, but 4,000 miles across the Atlantic, history is in danger of repeating itself as tragedy on the very island in which Toussaint L’Ouverture led a successful slave revolt against the mighty French Empire. Why do abject descendants of the Black Jacobin find themselves on bateyes in the Dominican Republic, where the only thing that is missing from the era of chattel slaves is the sound of the mayordomo’s whip?

I’ve not been to the cane fields of the Dominican Republic, nor to those of Florida where H2 workers from the Caribbean were hired in the 1980s and 1990s to work under atrocious conditions until adverse publicity “forced” the strategic substitution of mechanization for the machete. The labor lesson of the Sunshine State, still buried in boxes of documents in a West Palm Beach courthouse, is that because machines can’t talk back, “industrial relations” problems can be deflected. Again, rather predictably, the spokesman for Florida Crystals Corp. quoted in the Feb. 14 story poses precisely that scenario as the “solution” on Toussaint’s island, where Cuban Americans Alfie and Pepe Fanjul have extensive sugar interests.

But why, in 2008, are socially concerned filmmakers thwarted in their efforts to make the general public aware of what has hitherto been out of sight and out of mind? The question and answer ought not be rhetorical. But until “sugar films” like those mentioned in the Feb. 14 story are given the oxygen of publicity, they may just as well be. That is the bitterest lesson of all.

Ron Noon

Senior Lecturer in History

Liverpool John Moores University

United Kingdom