Love Lane Lives

The history of sugar in Liverpool and the effects of the closure of the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery, Love Lane

Molasses, United Molasses and RUMBULLION!

Written by Ron Noon at 13:52 on Monday, October 04th 2010

FIRST OF ALL THESE ARE THE INITIAL REMARKS ON A BLOG I DID JUST OVER THREE MONTHS AGO:

“The opening comment on our Love Lane Lives film is from a woman who declared shortly after the refinery closure in April 1981, ‘it’s dead now’! She meant Liverpool was dead, not Tate & Lyle but I wonder what she might have said about today’s historic announcement from Tate’s London Sugar Quay headquarters, that the once biggest sugar processor in the world, is literally selling off its sugar business? It will be left with “splendid” Splenda, the low calorie sweetener made from sucralose, and a substantial ethanol and industrial food ingredients business, which CEO Javed Ahmed emphasised as accounting for the majority of its annual sales and profit. If we had some ghostly interviewing techniques what would Henry Tate and Abraham Lyle make of a new company diet bearing their illustrious names but premised on eliminating sugar cubes and golden syrup?

In popular parlance Tate’s sugar cubes and Lyle’s golden syrup have gone together like bangers and mash but the newly appointed CEO who took over from Iain Fergusson at the end of last year has clearly decided to break away from company traditions and popular perceptions of its brand image. He does not see ‘Value added’ in the sugar refining industry, the brand with which Tate & Lyle is synonymous, but which historically has always been associated with the volatility of the commodity business.”

Tate and Lyle acquired United Molasses (UM) in 1965 but it had been coupled with molasses long before it bought the UNITED brand. At the very least in a roundabout way it was associated with the volatile and explosive nature of a liquid commodity comprising three letters, which was spelt by placing an R in front of UM! Sugar’s most obvious by-product was of course RUM and the Australian sugar and rum company Bundaburg was at one time in Tates portfolio, before they sold it off, (along with the iconic BUNDY RUM), in 2000.

Where does the word RUM come from? There are those who argue that it comes from the latin term for sugar, “saccharum officinarum” but I prefer the historic English slang word “rumbullion” as its source. According to W.R.Aykroyd in Sweet Malefactor, “rumbullion” was a word of Devonshire origin meaning tumult and “was shortened to rum a few years after the hellish liquor was first manufactured”. A writer in Barbados in 1651 expressed it this way:

“The chief fuddling they make in the island is Rumbullion, alias Kill-Devil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot, hellish and terrible liquor.”

The website of the West Indies Rum Distillery provides a graphic account of the volatility of that mid 17th century world when as we know, an island smaller than the Isle of Wight inaugurated THE SUGAR REVOLUTION. (Have a look at the December 29th 2008 blog: Liverpool, the Bajan sugar Revolution and the era of the Sugar Standard.)

“Just 4 years later, in 1654, the General Court of Connecticut (New England) ordered the confiscations of ‘whatsoever Barbados liquors, commonly called rum, kill devil and the like’. This confiscation was to protect the distilleries in New England and is the earliest known recognition of Barbados rum in the colonies. Kill Devil or Rumbullion was noted as rough and unpalatable and could overpower the senses with a single whiff and would lay men to sleep on the ground! It was believed to have been a stronger spirit than any other in the islands and was used to cure many afflictions in the tropics - colds, tiredness and sunstroke were all treated in slaves by kill devil in order that these ailments did not interfere with their work. All these accounts co-incide quite nicely with the introduction of sugar cane in Barbados which was brought to the islands by the Dutch settlements of Brazil and Guyana in the 1630’s.”

The phrase “kill devil” according to Aykroyd might still be heard to this day in Newfoundland “where because of seafaring traditions, rum is a favoured spirit and where many old words are preserved”. (I may have to undertake some participant observation when next I visit Albert and the lads in the Punch and Judy. As the son of Merchant seaman Henry Noon I need to undertake more research on Liverpool’s seafaring and drinking traditions.)

In the interests of balance and to guard against my obvious bias towards the Tropical Antilles rather than wet Fenland England, it does however take two types of molasses to tell the full story of sugar’s quintessential by- product. Sugar cane molasses are known in Britain as “blackstrap molasses” but we have to acknowledge its “dopelganger’, beet molasses. To the aficionado however the doplelganger which Napoleon helped foist on the sugar world in the early 19th century, (and which belatedly was introduced into Britain and wet Fenland England in the 1920s and 1930s) is decidedly not the real thing! Although equally fermentable, it “is unsuitable because of its unpleasant taste and smell”! Albert reminded me of that when he emphasised how Love Lane refinery could and did “process” the beet from the then British Sugar Company quota, and he said unlike their traditional sugar cane source beets stank! The stench of ammonia from beet molasses only re-inforces the provenance of Caribbean and Demerara rum and how when it comes to fermented drinks the cane is always king. Anyway that’s enough about Rum for now.

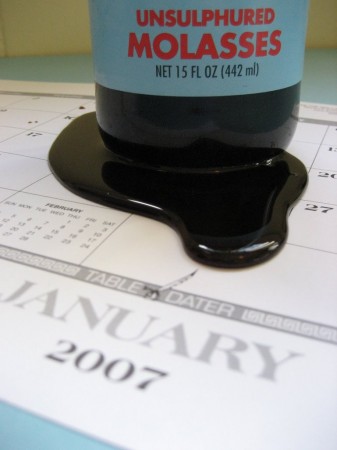

So to recap, Molasses is the main by-product of sugar production, used by the fermentation and livestock feed industries. UM was a firm like Tates that was made on Merseyside. If you ask ar Bobby Austin he will tell you all you need to know about the “refining process” and as an ace panman (sugar boiler) he knew when to “strike” to make the sugar crystals that we take so much for granted in our sugar bowls. Treacly molasses are obtained only after the crystallisation process and materialize as a dark gooey and heavy liquid. (Bobby was a far more effective “striker” than Ian Rush or Roy Vernon would have been if they’d “played” in Love Lane. The Love Lane “strikers” were world class and after the Lane Bobby continued to score sugar in Iraq, where his work was interrupted by a REVOLUTION, South Africa, and the Phillipines.)

Unrefined cane molasses contains some important minerals such as iron, zinc, chromium, and small quantities of magnesium, calcium and potassium. This is not enough to fill the “empty calorie” but certainly enough to differentiate it from that extracted from beet. UM was however much more than just rum and “brown sugar”. The extensive storage, loading and unloading equipment, spread over a vast geographical area, meant that the international molasses economy was dominated by a few players. As Phillipe Chalmin argues “the main problem of the molasses economy is the logistics involved: it is a costly product which it is difficult to stock and worth little…International trade in this commodity is therefore the preserve of firms which have enough money to handle the product from the sugar factory in the tropics to the warehouse of the end user”. So given that not many could afford to operate on such a scale, UM certainly did and was also an international trading firm with its own shipping lines.

Diversification out of sugar refining in the UK was a strategy Tates had planned and prepared for years before Britain joined the EEC in 1973. From the early 1960s a number of directors realised that refining was no longer the “cash cow” it had once been. Despite opposition from some of the old guard “sugar mill” directors, the acquisition in 1965 of UM, with its world wide network of activities and distribution points, opened up new horizons and new directions. It also completed another symbolic “local/global” dimension because UM had been founded by a “Liverpool Dane” with an attraction to molasses, Michael Kroyer Kielberg. Antony Hugill in SUGAR AND ALL THAT (the 1978 history of Tate & Lyle) describes how Michael had arrived in Liverpool in 1907 at the age of 25, “a quiet soberly dressed young Dane” He was about to apply for a job with Marquis, Clayton, “a modest firm of cattle-feed importers” whose address was 4 Chapel Street. The firm not only took him on but within three years made him a partner. “Now Kielberg became fascinated by molasses” and a global dynasty was formed. Keilberg was one of only two external directors on the Board of Tate & Lyle in the whole of the inter-war period. The other was Lord Birkenhead.

In 2004 Tates decided to unify its subsidiary companies including UM, Amylum, Alacantra and A.E.Staley, under the common name of Tate and Lyle and the liquid storage tanks that had once proclaimed United Molasses on Regent Road Bootle, helped provide a massive boost to the local paint trade. the biggest since the de-regulation of the buses, enabling fresh displays of the historic company livery of the Tates and the Lyles that had been sorely missing in Liverpool since 1981! .